Designing one’s own home is often described as a test. For Nebras Aljoaib, it is closer to a declaration. Set within a Riyadh townhouse, the project reads less like a styled interior and more like a self-portrait rendered in stone, proportion, and memory. It does not begin with a manifesto. It begins, as she describes it, when “a home feels layered and personal rather than styled… that’s where I begin.”

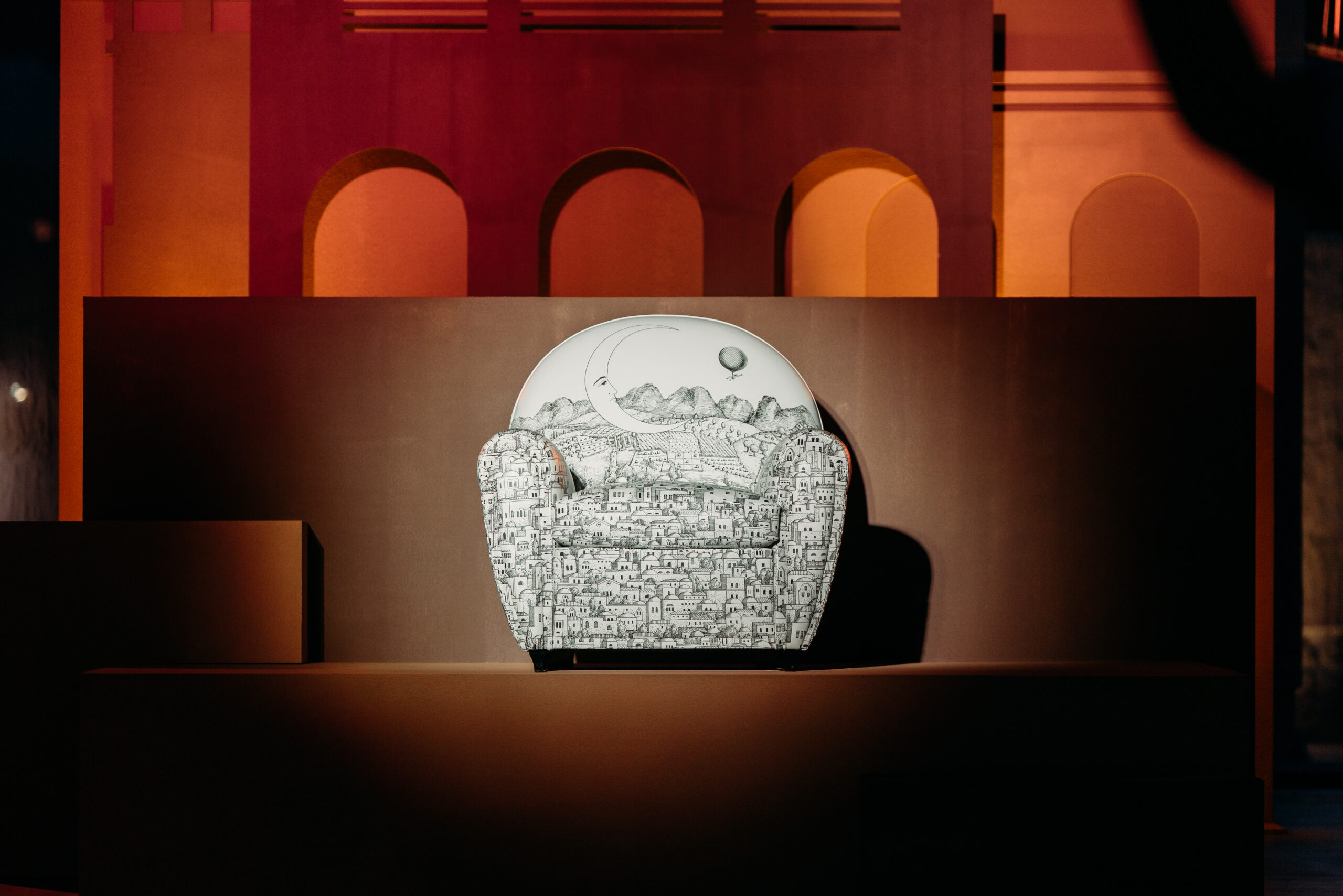

There was no fixed concept imposed from above. Instead, direction emerged from what she had already gathered through living: travel, collecting, returning to materials she trusts. “Design and art are inseparable,” she explains. Objects with memory — vintage finds, familiar stones, contemporary forms — become both compass and constraint. The result is an interior that feels raw in the most considered sense of the word: assembled over time, not arranged in a single breath.

For Aljoaib, a space ceases to be an arrangement when it no longer announces itself. “It becomes a home when nothing feels too precious to use,” she says. Architecturally, that ease depends on invisible discipline: proportion, scale, circulation. When rooms relate naturally and movement feels intuitive, “you’re no longer aware of the layout; you’re simply living within it.” Structure dissolves into rhythm.

Coherence, too, operates beneath the surface. There is repetition, material continuity, deliberate proportion — decisions made consciously — yet the effect must remain instinctive. “When nothing feels forced or disconnected,” she notes, coherence has been achieved. The framework exists to hold the house together, but never to perform.

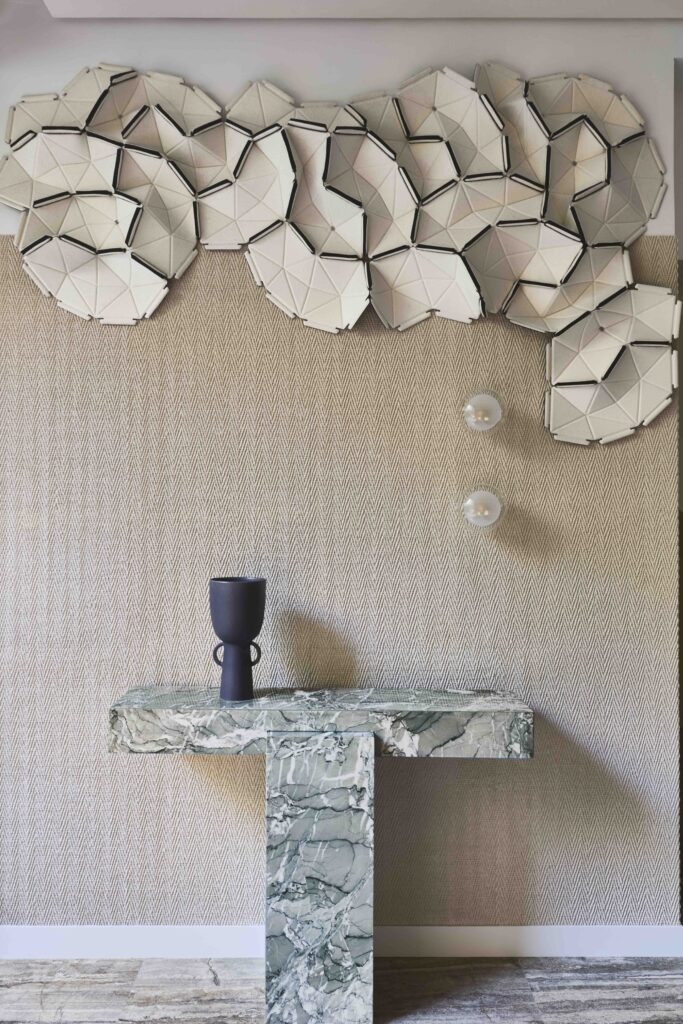

What she protected most fiercely was not a piece of furniture or a view, but a condition: “Mood and soul.” The house could not feel decorative, nor cold. Its emotional weight is carried through density — layered stone, textured finishes, shifts in scale that exaggerate certain gestures and soften others. Curated, yet never rigid, it retains what she calls a lived-in presence. “I protected the soul of the home and the overall timelessness of everything in it.”

Intimacy here is architectural rather than ornamental. “Intimacy comes from depth, not decoration.” Rooms draw you in through considered scale and deliberate composition; nothing is untouchable. Life is meant to take over. And time is not an afterthought but a collaborator. “I design for what feels timeless, not what feels current,” she says. Stone should deepen, finishes should soften, objects should acquire character. A good interior, in her view, becomes more beautiful as it ages.

If a stranger were to walk in, she hopes they would sense an attraction to materiality and contrast — boldness without excess, structure without rigidity. Pieces with history coexist with a certain playfulness. Nothing staged, nothing forced. She lives, as she puts it, “amongst what I love.”

When asked to reduce the house to a single word, she does not hesitate: “Collected.” Not merely in objects, but in sensibility — a life gathered, edited, and given architectural form.