What began as a personal renovation in Dubai’s The Springs quietly became the manifesto behind Well Simply Living. Designing her own home gave Sola Kbaitry something she had never had before: absolute freedom. “It provided me the freedom to test, fail, and succeed without needing to compromise with a client,” she reflects. In that space, she defined what would later become her signature language—one rooted in calm, light, and emotional clarity. Showing the house publicly did more than attract attention; it aligned her practice. “It moved me away from ‘selling sneakers to a dolphin’—chasing the wrong clients—to doing work I am passionate about.”

Central to the home is a radical openness. Walls were removed not as a stylistic gesture, but as a way of living. By merging kitchen, dining, and living areas, the house became “airy, versatile, and connected,” flooded with natural light and a sense of continuity that guides daily life.

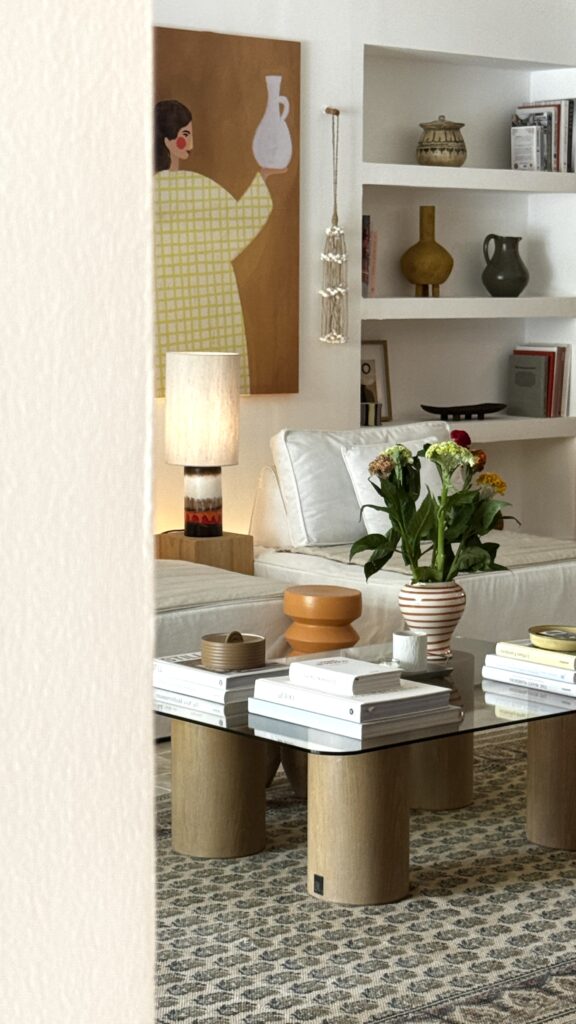

Natural materials were never negotiable. Wood, stone, greenery—elements chosen not only for beauty, but for how they feel. They “add warmth and vitality,” grounding the house in something sensory and human. For Kbaitry, design always begins with a story. “I primarily start by telling a story while resolving problems along the way,” she says—a balance that shaped what she describes as a “slow, simple way of living.”

Personal objects give the house its emotional depth. Hand-painted walls, cracked pottery, pieces kept rather than replaced act as “physical manifestations of our life story,” turning decoration into memory. The result is a home that slows you down the moment you enter—through light, air, and ritual. Incense, sage, silence.

Living daily with imperfection, she believes, is transformative. Wabi-sabi, for her, is not an aesthetic trend but a lesson: beauty exists “in the unfinished, the weathered, and the flawed.” It teaches resilience, self-compassion, and the quiet truth that “mistakes are proof that you’re trying.”