Words by Allegra Salvadori

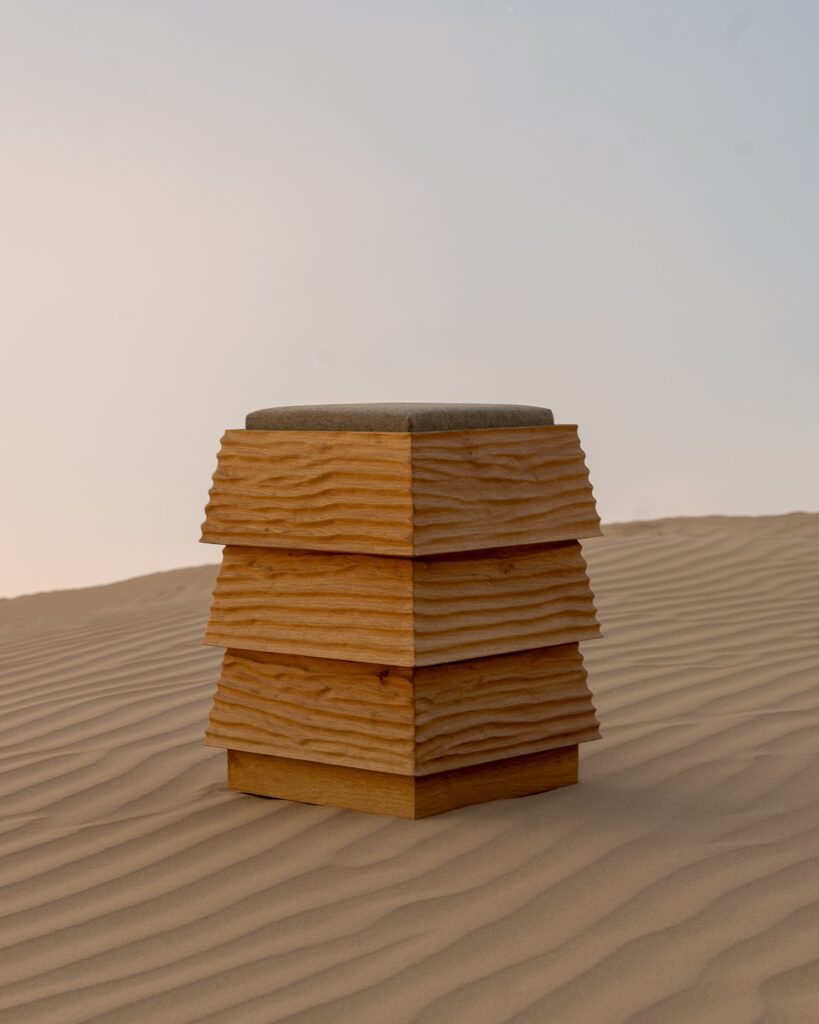

His objects look, at first glance, like sculptural artefacts that have quietly wandered into the realm of furniture and lighting by accident. Low, totemic stools with rippling surfaces. Cabinets skinned in timeworn metal. Pieces that feel as if they have lived elsewhere, in another life, before arriving in a domestic space.

We first spoke in September, in a conversation that unfolded more like a philosophical dialogue than an interview — circling around materials, non-conformism, and the strange, slow timing of ideas. A few weeks later, at Dutch Design Week, I finally saw Daniel’s work in person. His installation — monumental panels embedded with soft, integrated light — made immediate sense of everything he had been trying to articulate. Beautiful, yes, but also disarmingly functional; sculptural, yet resolutely purposeful. Think of a painting and where you would hang it. Now think again, with light in it. It was the moment when the theory of our conversation crystallised into form, and I understood why his presence at the fair drew such attention: his pieces don’t ask to be categorised. They create, instead, a space between.

For Daniel — Budapest-born, Germany-based founder of Heilig Objects — that tension is precisely the point. Galleries tell him the work is “too product design”; retailers say it is “too artsy”. He smiles at the contradiction. “I personally don’t mind,” he says. “That’s where I feel most comfortable, in this little niche in between.”

It is a niche defined less by typology than by attitude. His objects must live on both registers: as things we can use and as things that keep asking to be looked at.

“I need products–slash–objects that are interesting,” he explains. “They have to keep being interesting as an object, as a product. But still, it’s not that artsy that you don’t have any functional purpose.” The result is a body of work that treats function almost like a pretext — a way to bring sculpture into daily life without losing its emotional charge.

Time, patience and “speaking” materials

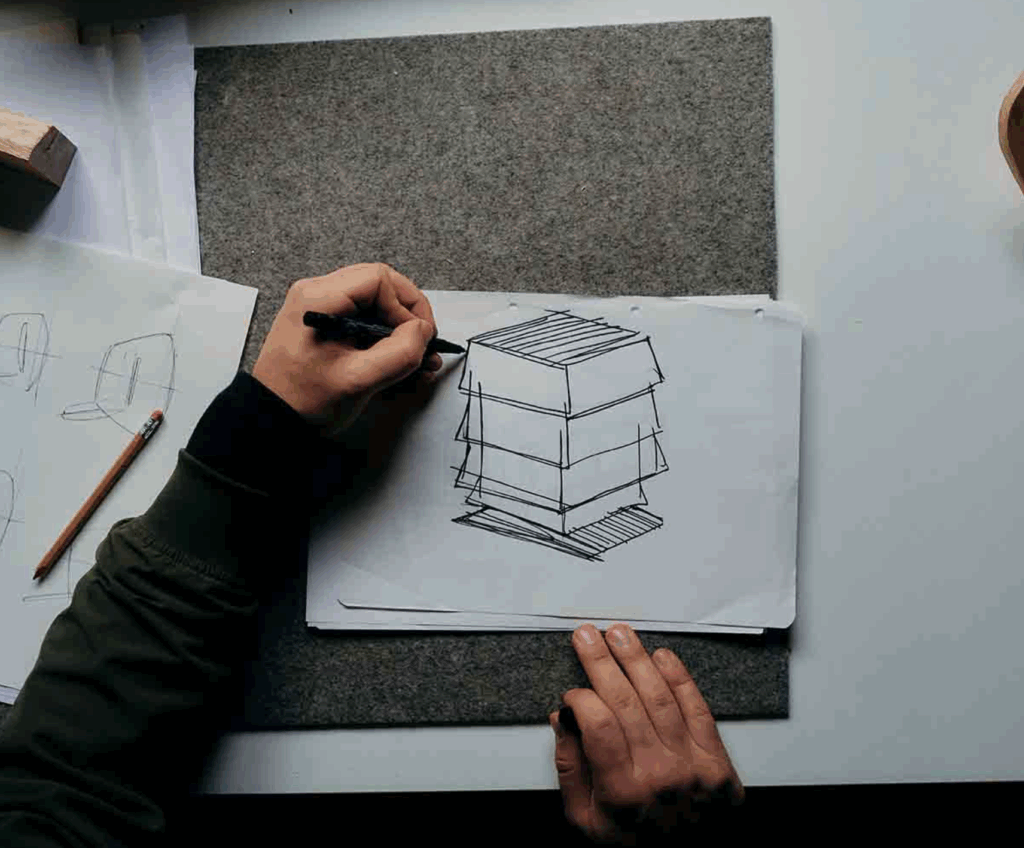

Daniel’s practice begins not with a sketchbook, but with an encounter: a material, a story, a texture that refuses to go away. The work then proceeds at a pace that would horrify fast-moving product cycles.

“Creating means that you have to invest time,” he says. “And I want to invest my time with purpose. It has to be meaningful.” Sometimes that meaning lies in a narrative; often, it lies in a material that has been used in one way “for decades, maybe hundreds of years” and suddenly suggests another life.

He tells the story of a chest of drawers whose façade is composed of baking trays salvaged from a cruise ship. “I immediately knew they were so interesting, so unique,” he recalls. “They were patinated, they really told a story — but I had no idea what to do with them.”

So he did nothing. He bought them, left them on his balcony, and waited.

“Every once in a while, I tried to get into a conversation with the materials, asking it, ‘Hey, do you have any response? What can we do together?’” It took months before he understood that the trays could become a surface — a kind of skin — for furniture. The idea needed to patinate alongside the metal itself.

This rhythm of waiting is not romanticised; it is structural. “The material needs time until it’s patinated, and I also need time until I understand what I can do with it.” Pushing too hard, too soon, breaks the spell. “Sometimes I feel this force to create,” he admits. “But it’s not the right time, not the right emotion, not the right feeling. Then you need to be super honest with yourself: we have to pause.”

In a culture obsessed with acceleration, this willingness to stop is quietly radical. His objects carry that slowness within them; they feel as if they have already lived a life before crossing the threshold of a home.

The “honesty” of objects

The first objects Daniel made felt like an antidote. “This is really hands-on,” he says. “It’s me in combination with an object, with materials, with a creative process. It’s so private somehow that I really felt this is good: with purpose, with meaning, with honesty.”

That shift from abstraction to tactility still underpins his understanding of what “collectible” means today. For him, collectible design is not about rarity; it is about authorship — how directly a piece channels the maker’s experience. “A collectible is a very emotional and direct approach,” he reflects, “rather than a standardized, industrialised product.” His own practice remains “something in between,” yet firmly anchored in the singularity of the gesture.

Created for non-conformists

Daniel describes himself as 100% self-taught — and he wears that as an advantage. Without the weight of a canon, he allows himself to think sideways. “I can be a free thinker in so many ways,” he says. “There is no one saying, ‘This is not okay, this is not allowed.’”

This refusal to conform is not a stylistic affectation, but a stance that dates back to his teenage years. “Being anti a little bit is always good,” he remembers. “Being anti a trend, being anti the masses — even though it’s challenging.”

Heilig Objects, his studio and brand, crystallises that teenage suspicion of the mainstream into a quiet manifesto: created for non-conformists.

The phrase distils his design triangle: difference; minimal and timeless aesthetics; and a maximisation of passion.

“I’m super allergic to any kind of trends,” he says. “It has to be timeless. But it has to be maximised in the passion and dedication we put into creating pieces.” That tension — between restraint and intensity — is palpable in the objects themselves: pared-down silhouettes that carry the emotional density of something far more baroque.

Teaching freedom in a world of constraints

From his base in Germany, Daniel collaborates with students at the local university of industrial design. There, he witnesses another friction: between academic training and true creative freedom.

“They can work and think well in industrial design,” he observes. “But when we say, ‘Today is sketch day, let’s be super creative’, I see a limitation. They are not supported in thinking that way.”

To unlock that inhibition, he sometimes proposes deliberately different ideas — an invitation to play, to loosen the mental grip of correctness. Increasingly, these prompts draw inspiration from the Arab world, where he has been exhibiting and travelling. “I’m somehow very attached to the Arabic culture and heritage,” he reflects. “Don’t ask me why; I’m still processing what’s behind this attraction.”

One recent exercise asked students to sketch chairs inspired by frankincense burners — an unexpected bridge between cultural heritage and speculative design. It reveals what fuels him: imagination as a tool for cross-cultural connection.

Wahiba Sands and the honesty of nature

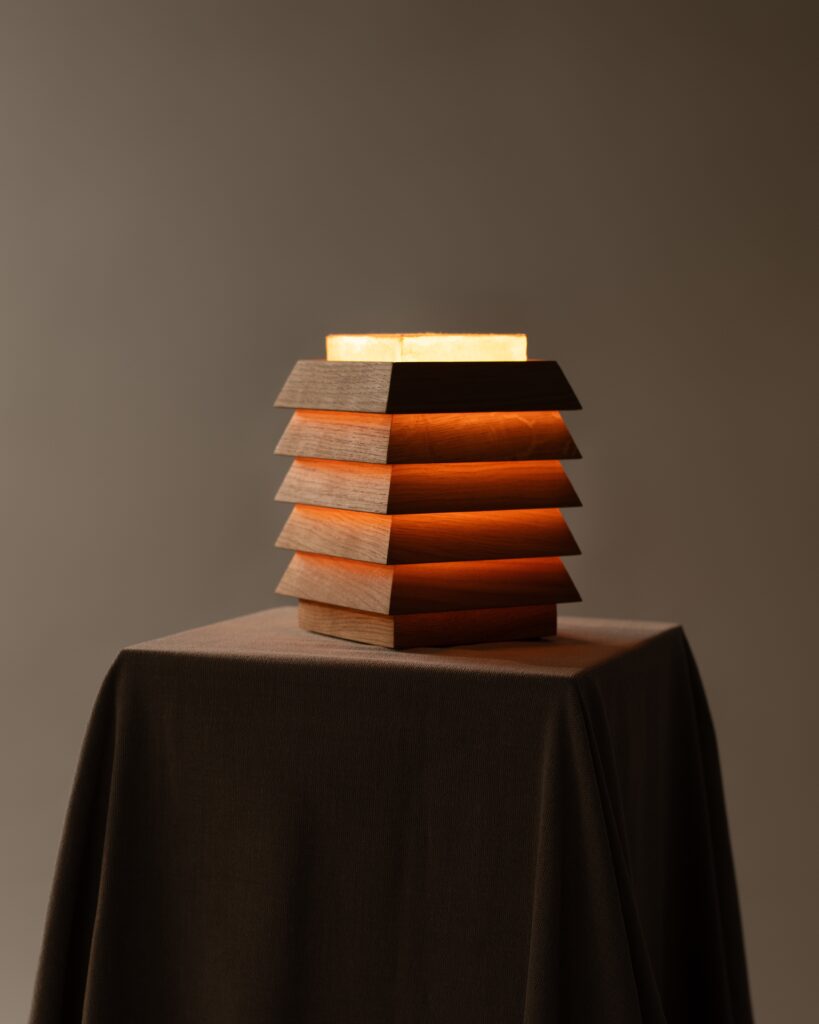

Among his recent works, the Pagoda stool — particularly the Wahiba edition — distils his attachment to the region into form. Inspired by Oman’s Wahiba Sands, it translates the undulating geometry of dunes into a rippled surface that invites both hand and gaze.

“I love to travel to the desert,” he says. “It’s such a great place where you can find your inner peace.” One night in Wahiba Sands, the way the dunes shifted between sunrise and sunset left a deep imprint. “The shape of the dunes really fascinated me,” he recalls. “I wanted to take this impression with me and apply it to the surface of the Pagoda stool.”

The waves that now ripple across the piece are less a literal imitation of sand than a meditation on nature’s authorship. “Nature is such a powerful source of creativity and honesty,” he says. “Sometimes there are things only nature can create.” His work is not mimicry but reverence — a translation of experience into object.

A practice that resists haste

By the time we met again in Eindhoven, where his illuminated panels quietly became one of the fair’s most magnetic installations, I realised something essential: Daniel’s vocabulary is not abstract. It is lived. His pieces behave exactly as he describes them — objects that illuminate, objects that function, objects that pause the world for a second.

And perhaps that is why they resonate so deeply with non-conformists: in a culture of speed, Daniel’s work proposes a different tempo. One in which slowness is not a defect but a strategy; where critical thought and emotional honesty have room to accumulate; where objects carry stories not because they shout, but because they were allowed to take their time.

Created for non-conformists, yes — but also for those who suspect that the most radical gesture today might simply be to pay attention.