When we talk of the pioneers of abstract art, names like Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich automatically come to mind. But there is another story, one that begins on the Mediterranean coast of Beirut, with a young woman who refused to believe that abstraction was a Western invention. Her name was Saloua Raouda Choucair.

More than a century after her birth, the late Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair still reminds us that art has no limits. Her story is one of courage, vision, and constant exploration — but also of deep rootedness to her homeland. And her art, radical for its time, expanded the very definition of what abstraction could be.

Born in 1916 in Lebanon, Saloua and her two older siblings were raised by their mother, Zalfa, under challenging circumstances after their father, Salim Raouda died in 1917 while a conscript in the Ottoman army. In 1934, Saloua enrolled at the American Junior College for women (now known as the Lebanese American University) where she studied science at a time when very few women even went to university. Fiercely intellectual, she read everything from quantum physics and molecular biology to Arabic poetry.

In 1948, she went to Paris where she enrolled at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts to study art. In 1949, she joined the studio of renowned modernist sculpture and painter, Fernand Leger, to study abstraction but she quickly left to develop her own abstract style. While in Paris, she participated in the Salon des Realites Nouvelles becoming one of the first Arab artists to do so and in 1951, she had her first solo show at Galerie Colette Allendy.

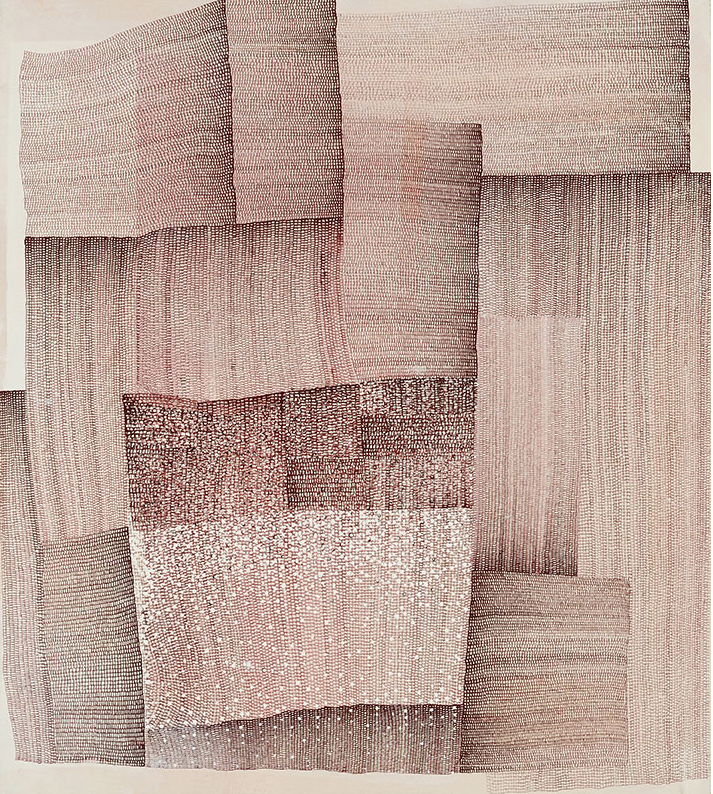

Saloua returned to Beirut later that year to ground her art in her cultural identity. A trip to Egypt years earlier had awakened her fascination with Islamic geometry which became the backbone of her abstract style. Merging the logic of geometric abstraction with the visual language of her heritage, Saloua created a body of work that is both universal in its modernity, and deeply rooted in Arab cultural identity.

Her practice never stopped evolving: painting, sculpture, jewelry, even carpets — not to become a carpet maker, but candidly because she wanted a painting on the floor. She created things that she needed, from dining room tables, to bags and accessories for her daughter. She was always very innovative, from using the seeds from dates to create buttons for a coat, to transforming a broken window that she found in the rubbish at the Lebanese airport into a coffee table. Her imagination had no bound, always experimenting, always curious and always playful.Don’t forget she was also a scientist, her work drew from mathematics and her fascination for Islamic geometry. She never confined herself to one medium, and her curiosity never stopped.

She was really a pioneer on all fronts… She got married late, had children later in life – defying the time she lived in in every way. An artist during the Lebanese civil war, she struggled to gain recognition but that never stopped her.

I’ve asked her daughter, Hala, to describe her mother in a few words – “A real original eccentricand creative multi-disciplinary scientific mind with the soul of a Sufi Poete” Hala said and that justput a smile on my face.

Today, Saloua’s work has been exhibited globally. She’s collected by the Tate Modern, the MoMA, the Met, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, and Mathaf, to name a few. But in this episode of Art with Sara, I’m visiting something unique: her foundation in Ras el Metn, a one-of-its-kind space in the Arab world, run by her daughter and granddaughters.

In 2021, Lebanon honored her with a postage stamp. And on June 24, 2024 — her birthday — the Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation opened to the public, not in Beirut, but in the mountains she deeply loved. Family-run, it anchors us in our own history and roots her legacy in the place that mattered most to her.

Saloua toured the world but always came back to Lebanon. Her dream was to see her sculptures in every Arab capital. And I hope one day that dream will become a reality.