Words by Allegra Salvadori | Images courtesy of Ramzi Mallat

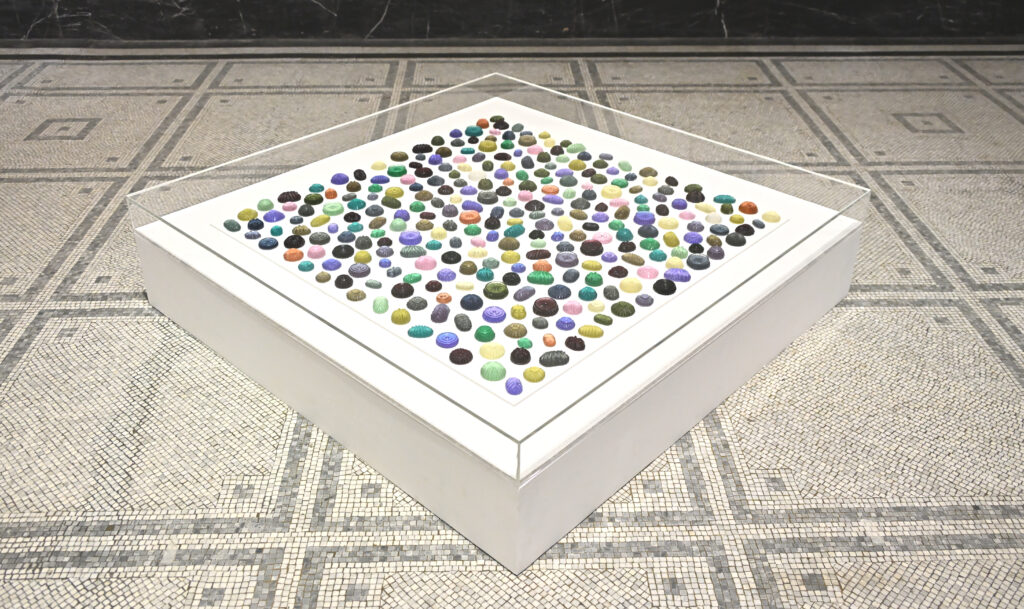

In the Medieval and Renaissance Galleries of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, amidst reliquaries, altarpieces, and centuries of European memory-making, a small cluster of glass pastries sits quietly on a plinth at ankle height. These are not relics of feast days gone by, but Not Your Martyr (2023), a migrating memorial by Lebanese artist Ramzi Mallat, created to honour the victims of the August 4 2020 Beirut Port explosion.

Our conversation unfolds on Zoom. I prepared a few questions, but the conversation quickly turned into something deeper — an exchange about grief, memory, and the role of art in shaping how humanity remembers. What strikes me is Ramzi’s capacity to speak across disciplines — drawing from history, politics, and folklore with ease — and yet remain anchored in personal experience. His voice carries both the pain of lived tragedy and the confidence of someone determined to transform it into a marker of collective memory.

Mallat’s installation — vibrantly colored ma’amoul pastries cast in glass — disarms through familiarity before confronting the viewer with dissonance. “I specifically chose these pastries as the sole figurative element of this memorial because of the interfaith property of ma’amoul,” he explains. “In a region fractured by division, ma’amoul transcends sectarianism by blurring the boundaries of religious celebrations and presenting a quiet testament to these interwoven cultures.”

Born in Beirut and now based between London and Lebanon, Mallat has long used his practice to navigate questions of memory, fragility, and endurance. He studied Fine Art at Lancaster University and completed an MA in Sculpture at the Royal College of Art, but his formation was as much shaped by Lebanon’s complex history as by Western art schools. “During that period — the economic collapse, the revolution, the blast, and COVID — I really broadened my horizons in understanding what it means to inherit oral histories as a post-civil war generation,” he recalls.

Listening to him, I realise that what moves me most is his rejection of compartmentalisation. Ramzi does not treat life, history, philosophy, the arts, and craft as separate realms — for him, they are interwoven ways of thinking. As a journalist and a historian, I recognise how history in his work is never a passive backdrop but an active force — animating its form, intensifying its urgency, and grounding its beauty in lived experience.

A Counter-Monument

The idea for Not Your Martyr crystallised in the weeks following the explosion, when broken glass covered Beirut’s streets. “For weeks, glass was the sound of the city,” Mallat remembers. “It was the material that injured the most people, the material that gathered everywhere. It made me reconsider the fragility and violence of glass, something we usually take for granted.”

Choosing glass as his medium became a deliberate metaphor. “Created in vibrantly colored glass, the medium’s tension between fragility and strength mirrors the emotional contradictions of mourning, where personal memories collide with collective grief,” he says.

But this is not a monument of nationalist grandeur. Displayed at ankle level, the work refuses the elevated heroics of state-commissioned memorials. “I didn’t want the burden of endurance framed as destiny — this constant idea that Beirut must rise like a phoenix,” Mallat insists. “I wanted vulnerability and intimacy. That’s why you look down at the work, in a solemn manner, rather than up at it.”

In this moment of our conversation, I sense the delicacy of his vision. He speaks of intimacy rather than heroism, of vulnerability rather than grandeur. His words stay with me because they resist the easy narratives that so often frame tragedies.

This counter-monument challenges both the absence of civil war memorials in Lebanon and the tendency to sublimate victims into martyrs. “Five years later, we still have no accountability, no justice, no closure,” he says. “The rubble may have been cleared, but we all still carry our grief with us like an open wound. Not Your Martyr is about giving that grief a form, however fragile, however intimate.”

Ma’amoul as Memory

If glass encodes the violence of the blast, ma’amoul embodies continuity, ritual, and heritage. “Making ma’amoul has always been a communal activity that brings together multiple generations,” Mallat explains. “Historically, families would take their dough to local bakeries, carving their initials into the wooden molds to mark each batch. These pastries are an intergenerational symbol of tradition and continuity, heightening the emotional resonance of this memorial.”

The floral motifs impressed into the molds carry a quiet symbolism. “They speak of springtime, but also of mortality — a memento mori,” he notes. “Like flowers placed on a grave, they mark both joy and loss.”

In choosing color, Mallat turned away from the grayness of conventional memorials. “I felt that the dullness of concrete and steel didn’t represent the richness of our culture,” he says. “I wanted to bring joy into the work, to use heritage as a medium to describe the beauty we have as a culture and immortalise it within this frame of grief.”

Diaspora and Urgency

Since relocating to London while maintaining a studio in Beirut, Mallat has become increasingly conscious of working as a diasporic artist. “I realized I had to deal with belonging through heritage rather than through the immediate context of my upbringing,” he reflects. This displacement, however, sharpened his sensitivity to traditions and their global resonance.

“I don’t want there to just be this narrative of war, destruction, helplessness, and erasure,” he says. “There is a richness that is culturally so diverse that I want to bring to the fore, which audiences outside the region are not always aware of. My mission is to push the boundaries of what contemporary art can be from a Levantine perspective — to reactivate heritage so it becomes revolutionary in conceiving the future.”

As he speaks, I am struck by the determination beneath his sensitivity. Ramzi is cultured, articulate, at times even poetic — but there is also a quiet urgency in his words. He knows that to carry memory is not just an artistic choice; it is a duty of care.

A Shared Vulnerability

At the V&A, Mallat’s luminous pastries sit in dialogue with centuries of European artifacts — and with the museum’s own imperial history. “Exhibiting in the Medieval and Renaissance gallery means entering a dialogue with centuries of European memory-making and asking what gets remembered, and what gets erased,” he reflects. “Inserting Levantine heritage into a Eurocentric canon becomes a discursive act of embracing multiplicity.”

For Mallat, this is not just about remembrance, but about refusing amnesia. “These luminous glass pastries become vessels for oral history, memory, and identity,” he says. “In both their translucency and opacity, they hold what is seen and what is lost.”

By the end of our exchange, I realise this was not just an interview but a dialogue — a meditation on grief, heritage, and the possibility of imagining futures differently. Ramzi reminds me that artists are not only creators of form, but guardians of memory, entrusted with opening perspectives where silence or repetition might otherwise prevail.

What resonates most — our common ground — is the urgency to challenge established narratives, to awaken critical thinking, and to see the world not as we have been taught, but as a tapestry of forces constantly reshaping our lives, a fragile and contested set of truths always in need of re-examination. In Ramzi’s words, this means accepting that fragility can be a form of strength, that memory can resist erasure, and that the vulnerability of peace — as delicate as glass — is worth protecting.